Ringing in a New Era

Good journalism can help reclaim truth in post-Assad Syria

Issue 29 – November 2025

A fragile space for public expression in Syria has reopened. Syrians can once again write and argue in public without fear. Yet six decades of repression and censorship have eroded society’s ability to speak to itself. Good journalism can help get the conversation going, but it will need freedom to succeed.

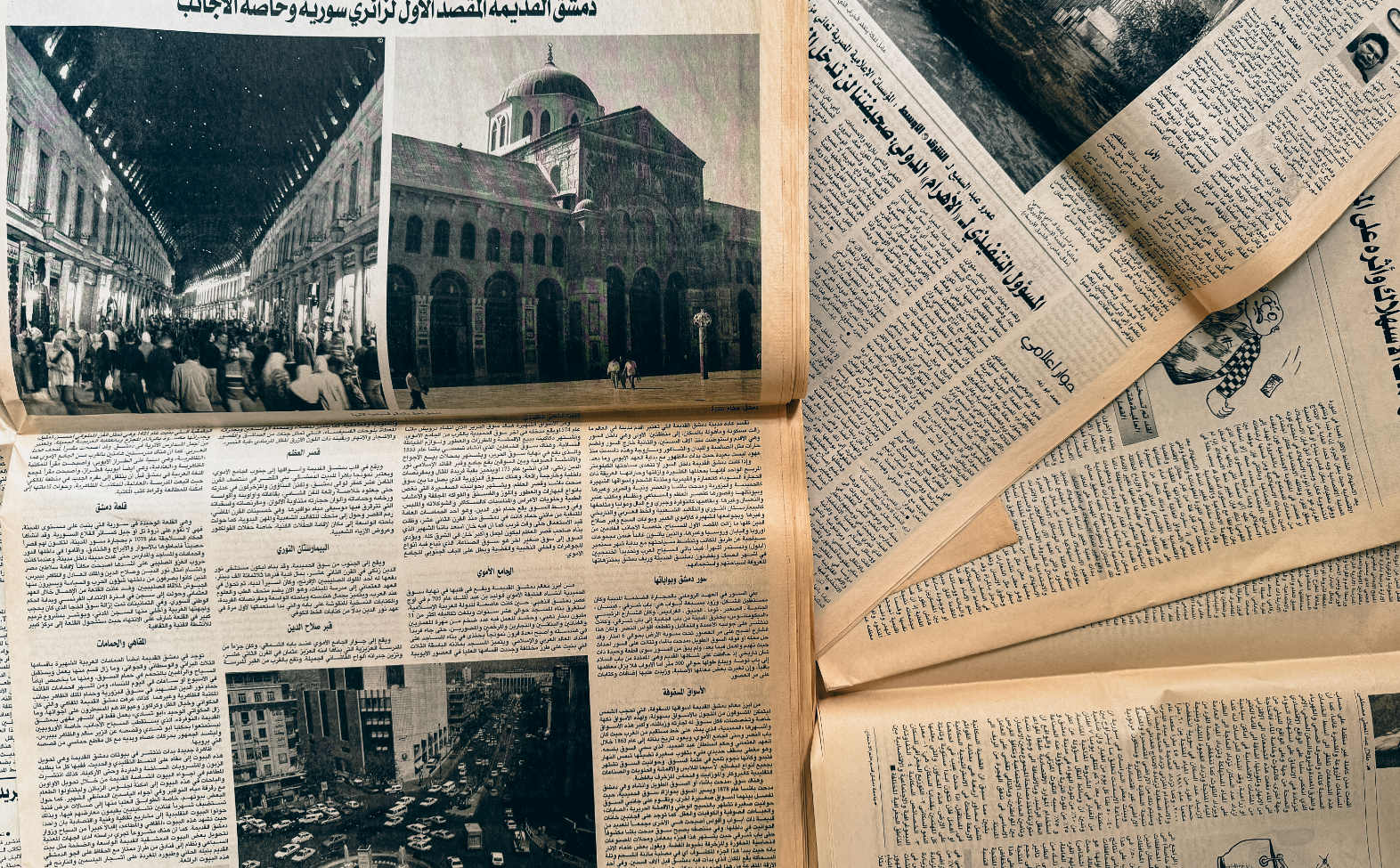

Most Syrians are unaware that their country once had one of the liveliest press scenes in the Arab world. In the interwar and post-independence years, and well into the early-1960s, Syria was home to hundreds of newspapers and magazines, catering to every political persuasion and intellectual current. By some estimates, more than 200 titles circulated across the country, from Aleppo’s al-Qabas to Damascus’s al-Ayyam. These reflected a society alive with public debate, intellectual curiosity, and a great deal of dark humour. For a brief time, Syrians could read, argue, and publish with a freedom rare in the region. It was a golden age of the written word in Syria.

That age came to an abrupt end in March 1963, when the Baath Party seized power and set up ‘committees’ to run the country. Not long after the coup, the satirical weekly al-Mudhik al-Mubki (“That Which Makes You Laugh and Cry”) ran a front-page editorial, the title of which was: “An opposition is necessary to illuminate the path before those who govern.”

The op-ed said:

We had hoped that, alongside these [Baathist] committees, an opposition to the government would also emerge – one that could engage it in debate, hold it to account, and express to it its own views, ideas, and plans. The matter [of government] is too weighty for a single party, or for one individual, to bear alone. Honest and fair opposition has today become one of the essential requirements of political life.

Within weeks the paper was shut down. The warning proved prophetic: satire was extinguished, dissent criminalised, and the press reduced to a chorus of flattery. For six decades, Syrians have lived in the long shadow of that editorial.

A space worth defending

Today, Syria stands again at the cusp of a new New Era. The end of the Assad regime’s absolute control has opened a space for public speech, albeit fragile and uncertain. The rebirth of journalism will be one of the surest indicators of whether a genuinely new era takes root. A society’s political health can be measured not only by the number of its institutions, but also by the quality of its conversation. If Syrian citizens are to become autonomous and responsible actors once again, they will need reporters and editors who can describe their future as it unfolds: critically, accurately, and without fear.

Many Syrians may still prioritise stability over the full spectrum of political liberties. After years of war and privation, that is understandable. But there is a difference between political constraint born of a sense of responsibility, and civic suffocation. Freedom from torture and arbitrary arrest are cardinal; so too is the freedom to speak, write, and argue. These are not luxuries of democracy but essential human rights. The right to report on the political, economic, and social transition under way, and to be properly informed about them, belongs to every Syrian, not to a select few with connections.

At its best, journalism can be an act of national reconstruction: it can help a society rediscover itself after years of distortion and fear.

Sadly, the media landscape that has emerged as yet is cacophonous. In the vacuum left by the state-controlled, Pravda-style publications, social media has flooded in: bot armies, conspiracy merchants and self-styled influencers compete for attention. Algorithms amplify outrage. The result is a swirl of largely meaningless noise. The phenomenon is not unique to Syria, but in Syria’s case, the cost is greater because it threatens to snuff out the space for truth that is only just re-opening.

The challenge, then, is not simply to defend free expression, but to nurture journalism of the highest calibre. This means speaking what is true and reporting for understanding. At its best, journalism can be an act of national reconstruction: it can help a society rediscover itself after years of distortion and fear, fostering the kind of collective understanding on which reconciliation and stability depend. Good journalism will sometimes err, but such mistakes are by-products of sincerity. To restore the right to honest error is to reclaim a freedom Syrians have been denied for too long.

If the interwar years sparked Syria’s first golden age of journalism, the 2020s may yet bring a second. The tools have changed, and the audience is now global, but the task remains the same: to bear witness, to hold power to account, and to remind Syrians that their opinions still matter. Syria in Transition aims to contribute to that renewal.