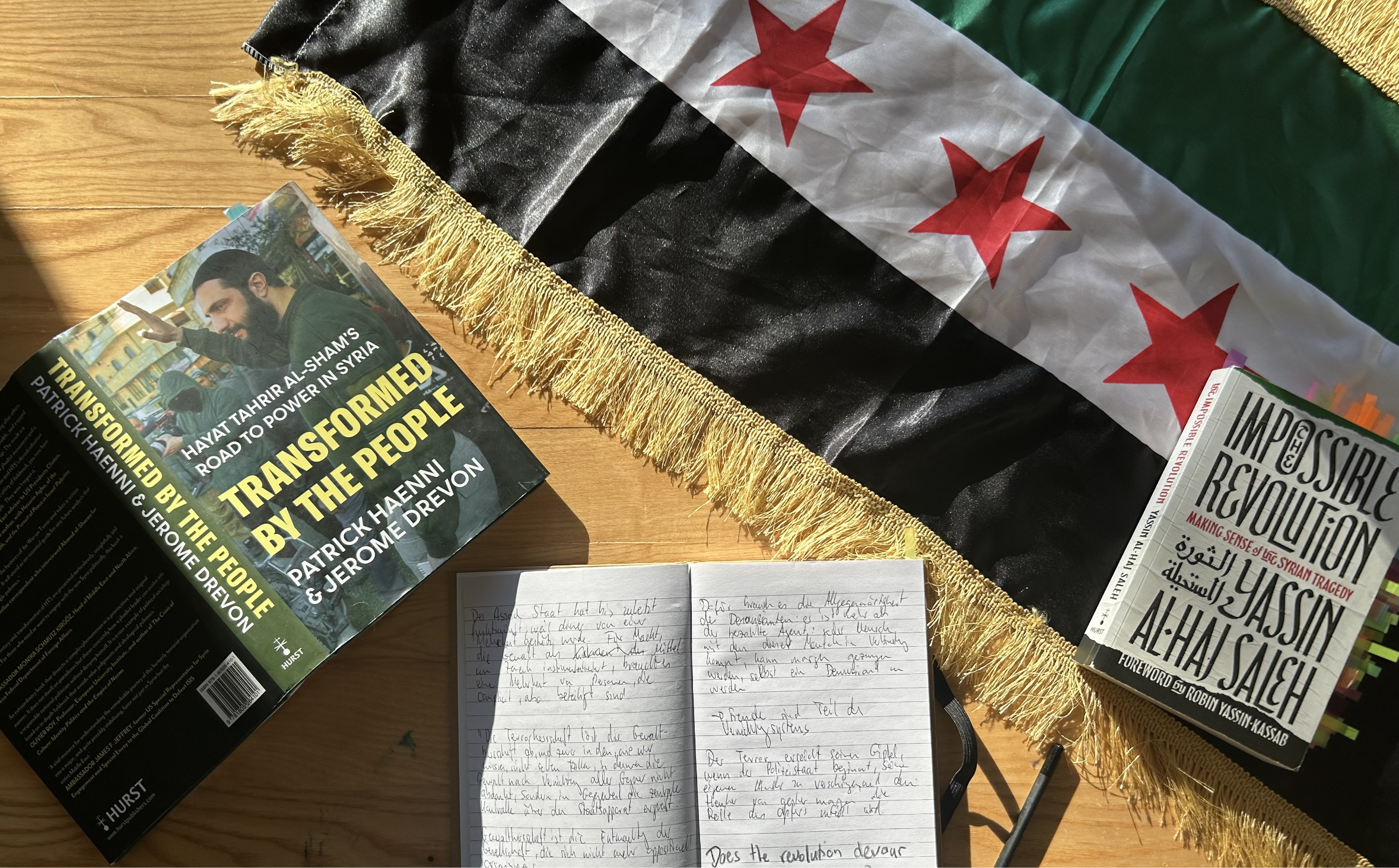

Transformed by the People – or performed for the people?

A critical review of Patrick Haenni and Jerome Drevon's book on HTS’s road to power

A movement once defined by jihad now speaks the language of governance, but has it truly changed? In a close reading of Transformed by the People, Dr. Sascha Ruppert-Karakas interrogates claims of moderation that rely heavily on elite-level access to HTS, highlighting how the prominence of self-justificatory narratives aligns with the authors’ declared aim of de-demonising the group around Ahmad al-Sharaa.

Well before Assad’s fall, the transformation of Syria’s Islamist northwest had already become a subject of sustained interest among scholars, journalists, and policy circles. The sudden domino effect of the offensive that brought down the regime within eleven days — and elevated a movement long associated with al-Qaeda to the central levers of power in Damascus — then turned that interest into a rush of we-told-you-so publications.

The opening salvo in this literature came in the summer of 2024, authored by Patrick Haenni and Jerome Drevon. Under the provocative title Transformed by the People, the two scholars advance the thesis of a “silent revolution” in Syria’s Islamist stronghold in the northwest, arguing that it pushed Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) from a Salafi-jihadist armed group toward a sophisticated political actor. In their reading, HTS did not triumph over society but emerged from it. It was a movement drawn into a process of moderation by Idlib’s silent majority. What had once been a Salafi-jihadist enforcer is reimagined as a curiously “centred” governing apparatus, compelled to adapt itself to the expectations, routines, and tacit norms of a conservative everyday life.

This “revenge of society,” as the authors call it, is presented as the engine of a deradicalisation not wrought by the Qur’an and the Sunnah but by everyday social pressure in Idlib’s streets and marketplaces. HTS is portrayed as having been drawn into a process of “relocalisation” through the gradual incorporation of traditional Sunni norms, the embrace of revolutionary narratives, and the marginalisation of radical hardliners unwilling to adapt. The transformation, they argue, was less theological than socially enforced; a process that drew HTS from the ideological periphery into the centre of a conservative-revolutionary social order.

To underline the nature of this shift, Haenni and Drevon reach for a grand historical analogy: the Thermidor phase of the French Revolution. As then, they claim, revolutionary fervour collided with political realities and was “forced to confront the limits of their transformative ambitions”. Society, rather than being the object of radical redesign, emerged as the true subject. In this telling, the HTS elite learned to orient itself around the “silent majority” in order to neutralise the vocal minority of jihadist hardliners — an adaptation that brought the movement stability and, eventually, power.

In this rendering, HTS’s deradicalisation appears as a political recalibration shaped by necessity, social inertia, and geopolitical constraint. What begins as an unplanned accommodation hardened into a strategic posture, culminating in a movement that, without becoming liberal, has nonetheless established itself as the new orthodoxy of rule in Idlib.

Access as an analytic constraint

The book’s empirical foundation rests primarily on conversations with members of HTS’s inner circle or people more or less sympathetic to the group's cause – i.e actors who are themselves invested in articulating and defending the movement’s alleged transformation. Although the authors argue that their fieldwork included a significant number of interlocutors unaffiliated with HTS, this diversity is difficult to discern in the analysis itself, which remains dominated by perspectives close to, or sympathetic toward, the movement. The resulting narrative tends toward an uncritical tone and, in several instances, conveys a notably accommodating reading of HTS’s militant history. Access to senior HTS figures was facilitated through a leadership-controlled invitation rather than a more independent or neutral research setting, placing the production of knowledge within a curated and asymmetric framework. Under this asymmetrical architecture of access, HTS retains structural control over what can be seen, said, and heard. While the authors acknowledge the resulting bias, they underestimate its significance. Authoritarian movements, after all, cultivate their outward image precisely through channels they are able to control.

Although the authors cite additional interviews with activists and civil society actors in Idlib, they largely exclude the opposition in exile, whose perspective, they argue, holds only “limited analytic value.” This choice systematically amplifies internal narratives, while underplaying the severe constraints that critical voices inside Syria faced. Precisely those actors best positioned to speak openly about repression, violence and authoritarian practices — by virtue of relative safety abroad — are marginalised.

This blind spot is, as the authors concede, deliberate. The “darker aspects” of the movement, including, human rights abuses and institutionalised intimidation and violence, are treated as peripheral on the grounds that they would distract from the politico-religious evolution the book seeks to highlight. Yet any account of transformation that omits HTS’s regime of coercion risks becoming analytically skewed.

In the end, the research design allows HTS’s leadership to speak largely through its own self-justifying narratives, from which the authors infer both transformative capacity and political potential. This risks unintended legitimation, even political exoneration, of the group - particularly troubling given the persistent coercive and authoritarian structures that continue to underpin HTS rule.

Personality cult with an academic seal of approval?

This phenomenon is not entirely new in Syrian academic research. In 2005 David W. Lesch published his The New Lion of Damascus: Bashar al-Asad and Modern Syria, a work built on privileged access to the regime’s innermost power circles. Parts of the book, with its biographical elevation of the young Assad, read like state propaganda stamped with academic legitimacy. Bashar appears as a selfless moderniser, carried by popular support a central trope of the regime’s personality cult. The picture painted by those who wrote about the Assads from a genuinely independent position was very different, and earned the regime’s ire. After his seminal Syria: Neither Bread nor Freedom was published in 2003, longtime British scholar of Syria Alan George was denied any further entry visas.

Transformed by the People is, in several respects, the counterpart to books such as Lesch’s from the other side of the fence. It is rich in empirical detail, offers sharp observations on HTS’s local embeddedness, and advances a plausible case for the movement’s potential role-model function among Islamist actors. Yet the book’s idea of transformation often feels only partially developed and leaves telling gaps. Rather than pursuing a clearly delineated research question on how HTS has changed and with what political consequences, the authors embed the movement in a broad narrative of contextual adaptation, in which description frequently substitutes for analysis. The argument is propelled less by an inquiry into the mechanics of authoritarian change than by the authors’ second, stated ambition: to de-demonise the group around Ahmad al-Sharaa.

The authors portray HTS’s evolution as a process of transformation. On closer inspection, however, it appears more a strategic self-optimisation under shifting political conditions than any real metamorphosis. The ideological reframing they interpret as signals of change function primarily as instrumental: they stabilise authority, broaden local resonance, and facilitate hegemonic consolidation, while leaving the movement’s ideological core intact. Under the pretext of offering a sober, realistic view of the ‘new’ in Idlib, the analysis ultimately sidesteps the more consequential question of what this reading implies for Syria’s political future, and whether the optimism the book advances can, in fact, be sustained by empirical evidence.

There is further reason for scepticism in the book’s treatment of individual personalities, which at times sits uncomfortably close to the emerging cult of personality around Sharaa now visible in parts of Western analysis. A central problem is the consistently favourable portrayal of Ahmad al-Sharaa himself. He is not depicted as the architect of a new authoritarian order — more in line with the empirical evidence that thus far exists — but as a remarkably gentle decision-maker pushed into difficult choices by external pressures such as radical commanders, geopolitical tensions, or the expectations of a conservative social milieu. Rather than appearing as an intentional actor with a clear power agenda, he is cast as a conciliator who seeks balance, rejects sectarian rhetoric, and even protects vulnerable groups such as the Yazidis in Iraq.

The problem lies not only in this narrative softening but in its empirical basis. These positive characterisations rely almost exclusively on accounts from Sharaa’s immediate entourage or from anonymised voices whose credibility the authors do not interrogate. The resulting portrait obscures structural violence and authoritarian practice and projects the responsibility of leadership onto a morally elevated figure. Power is personalised, when it should be analysed institutionally.

Manufactured moderation

The analysis of the societal “demand side” remains strikingly imprecise. The authors attribute HTS’s transformation to a form of social inertia that constrained the movement and drew it back into the realm of the “acceptable.” This, however, overlooks the fact that HTS and its precursor, Jabhat al-Nusra, themselves shaped the very social spaces in which consent, dissent, or accommodation could be expressed. What appears as a “silent majority” is better understood as the product of authoritarian pre-structuring: a conservative-orthodox spectrum was tolerated, while progressive, feminist, leftist or liberal-democratic milieus were marginalised, intimidated or eliminated. This is underlined by the integration of traditional Sufi orders – long a pillar of authoritarian stability under the Assads. For this reason, claims about HTS’s capacity to integrate a genuinely broad revolutionary constituency warrant scepticism. The realities have been highlighted by writers such as Samar Yazbek and Yassin al-Haj Saleh, who have repeatedly described the Syrian revolution as having been “stolen” by Islamist forces.

The paradigmatic counterexample is media activist Raed Fares, whose assassination by HTS, mentioned only in passing, exposes how narrow this supposed openness actually was. Those who complied were incorporated; those who articulated an alternative political future or challenged the cognitive structures HTS inherited from the Assad regime — and reworked after the latter’s downfall. Any analysis of “transformation” that ignores this authoritarian prefiguration of the social sphere inevitably overstates the agency of “the population” and underestimates HTS’s strategic calculus.

Ideological rearticulation under violent premises

The material presented ultimately reveals that ideology is neither secondary to, nor displaced by, pragmatic politics. On the contrary. The essence is a mode of rule in which decision takes primacy: doctrinal principles are deliberately downgraded and redeployed as justificatory resources. This, however, is not an escape from ideology but an ideological posture in its own right. No political actor operates outside ideology, and Carl Schmitt’s concept of decisionism offers a useful lens for understanding this configuration, in which authority no longer rests on doctrinal consistency but on the leadership’s ability to decide, impose, and justify exceptions.

HTS, then, has not become post-ideological. It has evolved into an authoritarian movement that employs ideology in highly functional ways, foregrounding those elements that secure its rule. What the authors describe as “retraditionalisation” is better understood as a re-articulation of an existing ideological matrix rather than a departure from it. This raises the question whether we are witnessing a genuine break with jihadism, or merely a recalibration of what is central and what is peripheral within the same ideological framework. As Yassin al-Haj Saleh has noted, a structure can remain Salafi in form even when it no longer speaks Salafi doctrine in every detail.

The decisive question, then, is not whether HTS still invokes Salafi or jihadist traditions rhetorically, but whether its underlying logic of rule has genuinely changed. As long as political order is anchored in the personalised and unaccountable sovereignty of Sharaa; as long as Islamic legislation provides a non-negotiable normative framework; and as long as dissenters are disciplined through a coercive apparatus, the movement remains structurally aligned with jihadist modes of governance, regardless of how moderate or pragmatic its self-presentation may appear.

Deradicalisation with a radical base?

Evidence for this interpretation includes the persistence of sectarian brutality. The recent massacres of Druze communities in Suwayda, attacks on Alawites along the coast, and assaults on democratic activists show that this violence is not confined to a marginal radical fringe, but is embedded in the structures of the new governing order.

Haenni and Drevon acknowledge the emergence of a new reservoir of Sunni-supremacist violence, yet leave the reader to wonder how, in concrete terms, this differs from the kind of radical jihadism the movement claims to have overcome. Their explanation that this is a result of a “re-radicalisation from below” places their own conclusion about deradicalisation under considerable strain. From a political-science perspective, it is difficult to argue that a movement whose security organs have demonstrably participated in, or at least tolerated, large-scale sectarian violence can be meaningfully described as “deradicalised” merely because its central leadership calls for restraint while shifting responsibility to lower levels.

Where the book itself hints at the General Security’s involvement in the coastal massacres, the authors consistently opt for a minimal interpretation. Responsibility is attributed to excesses by mid-level commanders, while the absence of a definitive “smoking gun” is taken — despite substantial evidence to the contrary — as proof that the top leadership was not directly involved. More plausible authoritarian explanations, such as the deliberate delegation and fragmentation of violence to diffuse responsibility and preserve deniability, are set aside.

This imbalance becomes even more pronounced in the authors’ attempt to normalise persistent sectarianism within HTS’s ranks through an analogy with the European radical right. They argue that the mainstreaming of right-populist parties leaves behind a residual xenophobic core without jeopardising broader moderation and that this logic also applies to HTS. This assertion is, at best, highly questionable. Much of the research on the European radical right interprets precisely this dynamic as a warning sign: leadership moderation often functions as a communicative strategy to widen appeal, while internal radicalism continues to advance through institutional or “legal” channels.

Applied to HTS, this suggests that the persistence of severe sectarianism — manifesting in both governance practices, selective coercion and violence — is not a residual remnant of an abandoned jihadist past, but a structural feature of a new authoritarian project of rule that offers little cause for optimism regarding Syria’s political future.