The Damascus book fair was a festival of freedom

17. February 2026

Queues, Kurdish titles, Ibn Taymiyyah, prayer halls and free buses to the exhibition ground. The Damascus book fair offered a compressed portrait of a country testing its new limits of plurality and free speech.

Observers and bibliophiles from the nation of “Read”—the first word revealed to the Prophet—agree that Damascus’s recent book fair resembled a national wedding, or perhaps an Egyptian mawlid, or a summer festival. The bridegrooms were the writers themselves, so much so that some wits renamed it the “Writers’ Fair”. Across social media came the refrain: You’ll find my book in Pavilion Such-and-Such at the Fair. A sardonic author posed the obvious question: where, exactly, were the readers?

For years, Syrian intellectuals lamented the absence of a public sphere under Assad. The Syrian people were corked inside a glass bottle called television. The country’s squares – literal and intellectual – were hollowed out. In every European city there is a great square at its heart, often by the bus or railway station, where citizens gather after a long day, demonstrate against the government, celebrate feast days, or simply talk.

In Syrian cities, by contrast, bus stations were shifted from their central places to the outskirts – ostensibly to ease congestion, though one suspects political motives. Al-Hijaz Square in central Damascus, once the departure point for the train to Makkah, became a museum devoid of artefacts: a relic of a vanished civilisation. There is talk now that Ankara and Damascus are working to revive the railway line destroyed by the English spy of Seven Pillars of Wisdom, better known as Lawrence of Arabia.

Salafists at the book fair

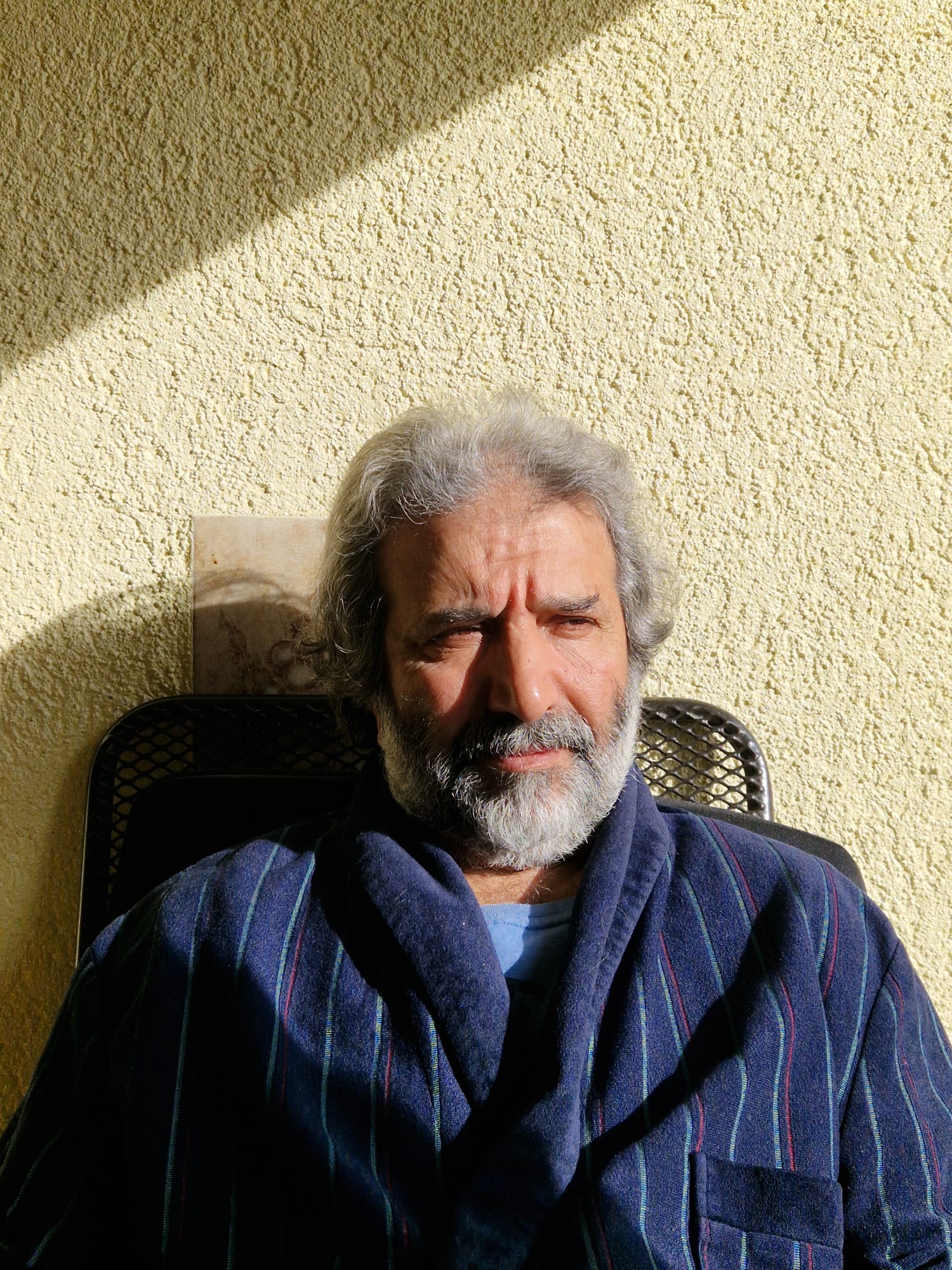

The traces of this “melancholy” wedding were evident in the writers’ online celebrations: proud displays of covers and portraits in what one joker dubbed “show-phony-ism” – from the Arabic imperative shufuni: look at me.

One singular innovation was the Kurdish section. For the first time in Syria’s history, books in Kurdish were displayed in a dedicated pavilion, staffed by attendants in traditional Kurdish dress. It was the fruition of a sixty-year national aspiration.

Those who complained about the profusion of works by the forebears – or of Salafist literature – were a small minority from secular and religious minorities alike. They grumbled about the stand devoted to Ibn Taymiyyah, among the most prolific authors in Islamic history after Ibn al-Jawzi. He died in imprisonment in the Citadel of Damascus in 1328, having been denied his books and writing tools. His funeral drew vast crowds. He had fought invaders and challenged the rigidities of political and juristic authority. A day may come when he is celebrated as the world once celebrated Nelson Mandela. Mandela was neither jurist nor philosopher nor theologian; Ibn Taymiyyah was the singular man of his age, an orphan of time itself, and remains a hero to much of the Syrian public. Some detractors sneered that the fair – once dubbed in the Assad years the “Progressive Book Fair” – had become the “Reactionary Book Fair”.

Ibn Taymiyyah is remembered for a line that reads like prose poetry, fit to be inscribed upon the eyelids with needles: “What can my enemies do to me? My prison is seclusion; my exile is travel; my killing is martyrdom.” To which one might add: and my persecution is publicity.

The mawlid of the book

Visitors to the book fair can now pray openly. In the 1980s prayer was forbidden; in the 1990s it was frowned upon in the public spaces of the “progressive socialist” state. Worshippers at earlier book fairs would spread hurried rugs in neglected corners. Today there are proper prayer halls.

The book fair is a mawlid (birthday of a saint of prophet) ceremony in which the visitor wanders like Alice in Wonderland. Syria now seems to have two feasts within a single year: the anniversary of revolution and the fall of the regime, and the feast of the book fair: an emblem of liberation. The Syrian people toppled one of the most odious dictatorships in modern Arab history at the cost of hundreds of thousands of martyrs and the ruin of stone and flesh alike.

Some complained about the fair’s location at the Exhibition City near the airport, though free transport was offered. Others about the price of books, which were out of step with purchasing power. One thing is certain: Syrians love books. Even those who do not read may purchase empty volumes for display, adorning their homes with the theatre of culture. No author was heard to protest the absence of his book at the fair.

The perfume merchant, it is said, never truly loses: if he makes no profit, he at least retains the fragrance. So it is with the visitor to the book fair. Even if he leaves empty-handed, he carries away the scent.