Rojava is emulating Ataturk in its distaste for Arabic

11. December 2025

As Syrian Kurdish leaders distance themselves from Arabic and Islamic heritage, their cultural revolution appears like an echo of Ataturk’s long-abandoned experiment.

The diverse peoples of Europe, speaking their Latin and Slavic tongues, came to embrace the Christian story despite it being entirely alien to their native culture. Their kings converted, and their nations and tribes underwent a cycle of sometimes violent conversion, at the end of which Christ’s actual origins and lineage hardly mattered. His Palestinian birth and Nazarene roots faded before his divine identity as the Son of God.

One is reminded of the anecdote recounted by the Syrian poet-diplomat Omar Abu Risha about his first meeting with President John F. Kennedy in 1961, when he presented his credentials as Syria’s ambassador. Kennedy asked about the Syrians; Abu Risha replied, “Our Syrian ancestor, Jesus Christ, is your Lord, sir.” Kennedy, amused, admired the elegance of the answer.

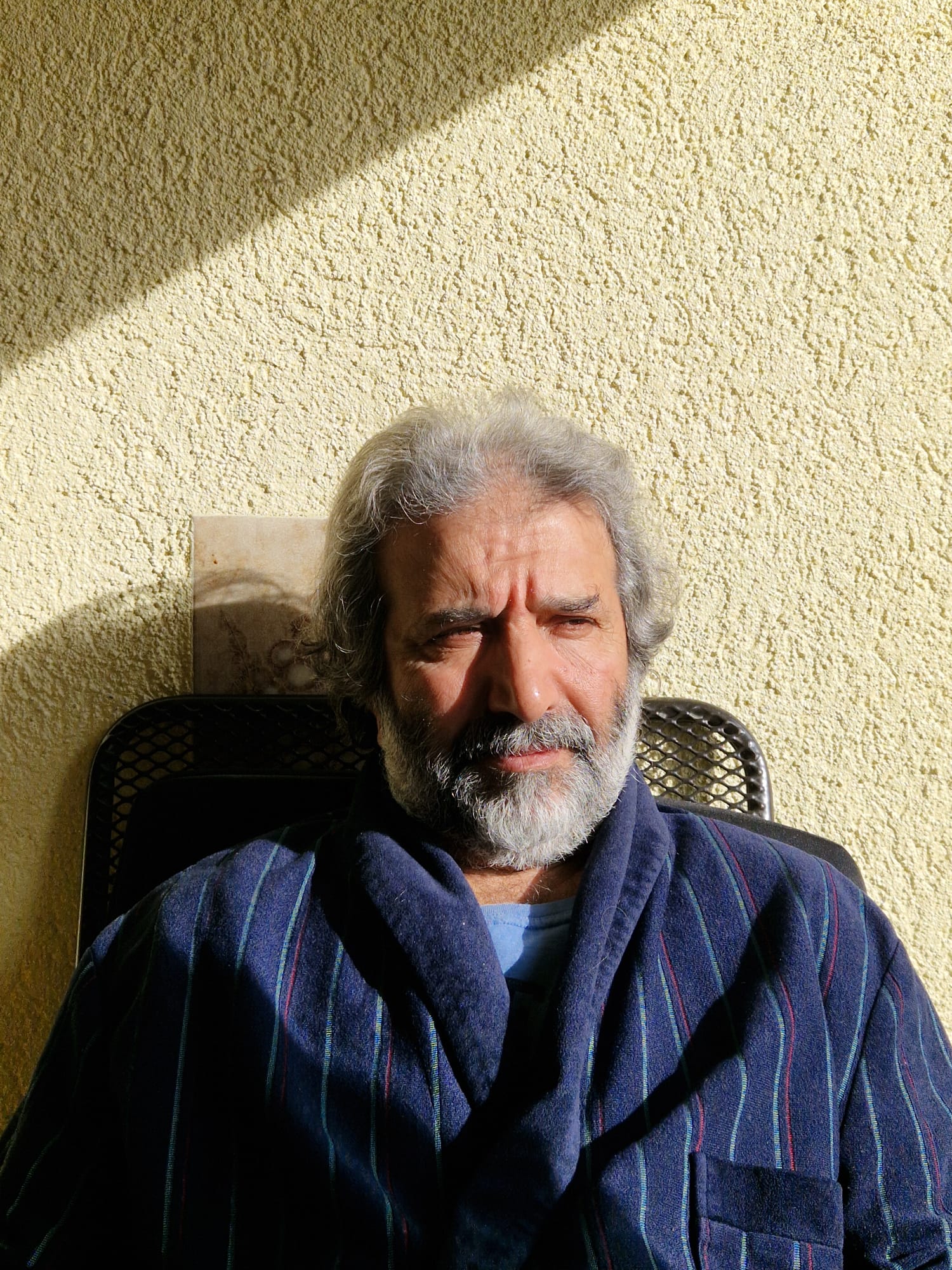

Ataturk as an unlikely model

Similarly, the Kurds embraced Islam in great numbers, and the tradition produced many prominent Kurdish figures: Yaqut al-Hamawi, Ibn Khallikan, Ahmad Shawqi, Abdul Basit ‘Abd al-Samad – topped, perhaps, by Salah al-Din al-Ayyubi.

Yet with the rise of modern nationalism, especially after the creation of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) in Turkey, contradictions began to sharpen that became even more pronounced after 2011. Despite its Marxist-Leninist foundations, the party found support from Washington. Despite its declared atheism, it adopted an ethnic nationalism often hostile to its Islamic Turkish and Arab surroundings, though more ambivalent towards Iran. The party even leaned toward a Shi‘i reading of history, elevating Ali as a revolutionary symbol against Umayyad “Arab tyranny.”

The PKK’s adoption of the Latin script mirrored Ataturk’s break with the Ottoman past and march toward the West. Just as the Turk abruptly woke one morning wearing Western dress and writing in Latin letters while still living the realities of a developing society, one might ask whether the Kurds of “Rojava” have taken Ataturk – ironically, a historic adversary – as their model. History enjoys its paradoxes.

Cutting ties with Arabic

In reality, the Kurds are overwhelmingly Sunni Muslims: they fast in Ramadan, celebrate the Eids, and maintain vibrant local traditions. Yet in recent years, a marked estrangement from Islam has emerged, particularly with the proclamation of “Rojava” and the Autonomous Administration, which aspires to federal status and, some suspect, to future separation. Its intellectuals and media figures challenge Syria’s official name, the Syrian Arab Republic, despite the Arab majority, while applying a Kurdish label to a region inhabited by Kurds, Arabs, and Syriac Christians alike.

This Kurdish nationalist turn draws neither from religion nor from shared history, nor the neighbourly wisdom that long sustained coexistence.

A telling incident occurred when a well-known preacher was invited to deliver the Friday sermon at the Qasmo Mosque in Qamishli. He preached in Kurdish. He might easily have recited Qur’anic verses and Hadith in Arabic, explaining them afterwards in Kurdish. Arab congregants walked out in protest.

Meanwhile, Kurdish commentators on satellite channels increasingly speak of an “Arab invasion” or “Arab occupation” of Kurdish lands, not unlike the way Arab nationalists once described Ottoman rule as “Turkish occupation.” This rhetoric pits religion against Kurdish nationalism. Salah al-Din himself is now accused by some of “betraying the Kurds” by establishing an Islamic rather than an ethno-Kurdish state.

Some voices go further, insisting that Abraham was Kurdish because he came from Mesopotamia, or that the Prophet Muhammad must have been Kurdish because he descended from Ishmael, son of a purportedly “Kurdish” Abraham born in Nineveh. It is hard to imagine an Afghan or Indonesian Muslim resenting the Arab origins of the Prophet; many travel thousands of kilometres to Arab lands precisely to learn and memorise the Qur’an.

A costly mistake

Similar anxieties once surfaced among Turks rebelling against their Ottoman past. Some rejected Arabic outright to ingratiate themselves with Ataturk’s new state. When a Turk was once asked, “Who is your Prophet?”, he answered, “Muhammad.” And when asked, “Was he an Arab?”, he replied, “God forbid! He was a Turk!”

In Syria’s northeast, after Bashar Assad entered into a deal with the PKK-aligned cadres from the Qandil mountains in 2012, Arabic signs were taken down, teachers of Arabic were punished, Arabic schools closed, and today anyone marking the anniversary of the regime’s fall is penalised.

This Kurdish nationalist turn draws neither from religion nor from shared history, nor the neighbourly wisdom that long sustained coexistence. Nor, indeed, from political wisdom.